Solstice 1906-1922: planes, Druids, automobiles ... and more clouds

As last year's essay documents, the 20th century had started cloudy in solstice terms, with the exception of 1903; and nothing changed in 1906. The Clifton Society reported that "over two hundred persons went … to see the sun rise" on the morning of 21st June, but it was cloudy and misty. There were many cyclists present and a number of motorists. However, the fall in numbers attending, which had accompanied the enclosure of Stonehenge and introduction of admission charges in 1901, continued.

__

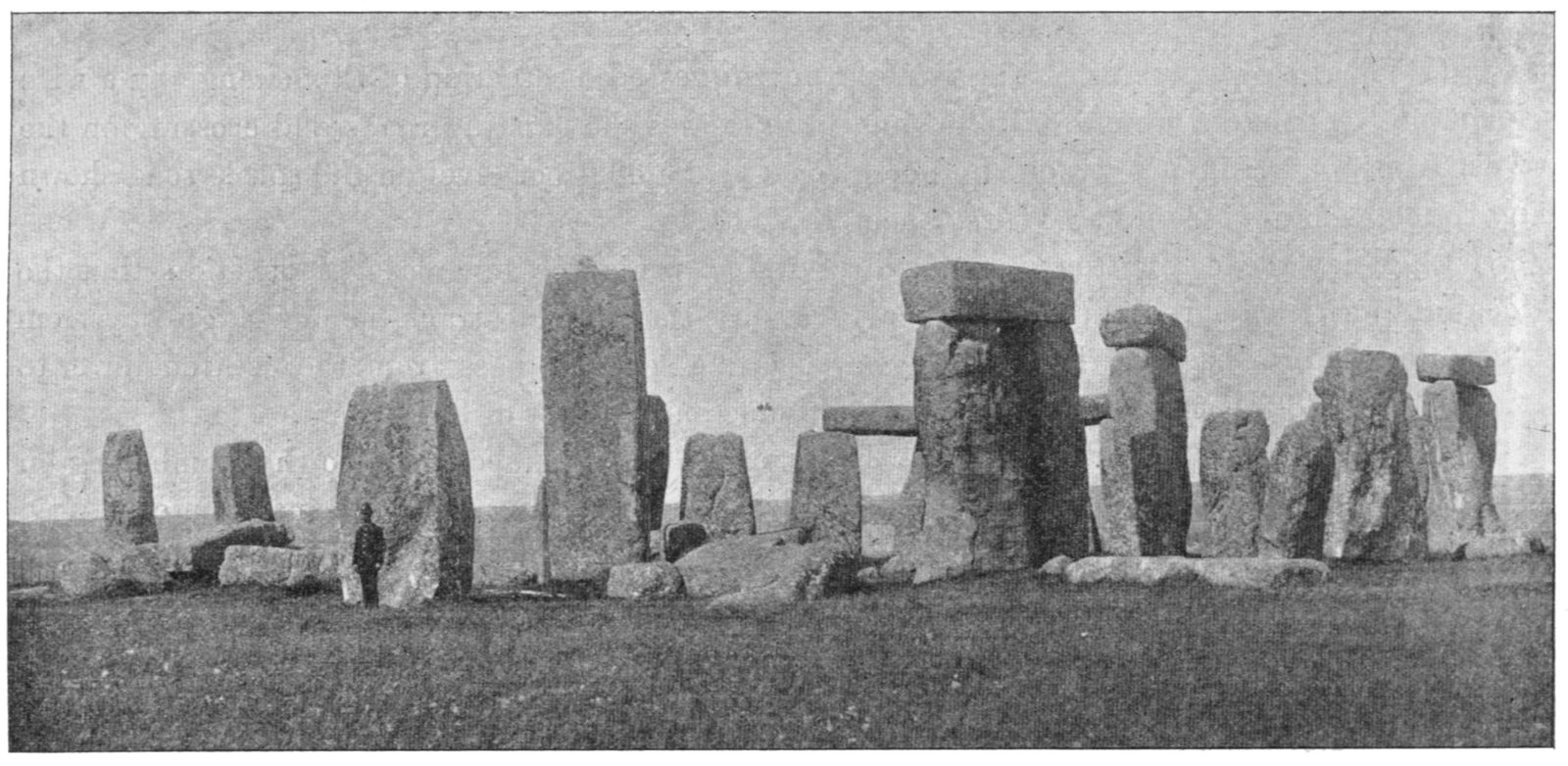

Stonehenge in 1901 [from Gowland 1902]

__

The following year the Salisbury Times’ headline immediately gave the game away: "In Quest of Old Sol. ‘Times’ Man’s Gloomy Vigil at Stonehenge." Rain had fallen earlier in the night but the correspondent nevertheless set off soon after midnight and was greeted by three or four cyclists at Stonehenge around 1 o’clock. Over the next couple of hours more cyclists arrived, from as far away as Dorchester, along with a number of traps, and "it was not long before we smelt motors". The fence continued to come in for some adverse comment - still rankling "in the hearts of those who have been accustomed to wander at will without payment", though the aptly named Supt. Longstone blamed the poor weather in recent years for diminishing attendance. This time, however, the usual two to three hundred were exceeded, but despite breaks in the cloud the sunrise was obscured: "Twenty minutes later Stonehenge was practically deserted. Even the sun wasn’t there."

__

In 1908 the Times was getting cynical: "If the British Empire is such that on it the sun never sets, there is a spot in it, and not very far from Salisbury, on which it never rises - well, hardly ever." Nevertheless, the numbers attending continued to climb and up to 2000 people were present that year; the wire fence groaned "under the weight of cycles propped up against" it. The paper anticipated the potential impact of the Daylight Saving Bill [in fact not implemented for another 8 years] by which "the sluggards are made early risers by Act of Parliament". Even without that additional hour, however, "the road is alive with cyclists, mostly male, but many lady riders make interesting variants on the other sex." The correspondent speculated whether "Tommy on 'sentry go'" at the Army camp, "unconscious of the native’s custom to gather on June 21st, and seeing all these people about, must have feared an enemy was concentrating for an attack…"

__

By 3.30 am everyone was present and "Inside the little toll house… the janitor and lady assistants were brewing tea and coffee for a big crowd." But once again "that big sheet of cloud refused to budge" and the crowd got back on their bicycles and "silently stole away." There was further disappointment, as the Warminster and Westbury Journal reported "many complaints about the slackness of local caterers", with the public houses besieged by "returning pilgrims" while "the landlords did not believe in too early rising, and none had forethought enough to make provision…"

__

We have another account from 1908, this time in book form, by the Anglo-Argentine writer and naturalist William Henry Hudson, in his ‘Afoot in England’. He writes that the custom of visiting for sunrise on the longest day is "a declining one: ten or twelve years ago as many as one or two thousand persons would assemble... but the watchers have now diminished to a few hundreds, and on some years to a few scores." He links the modern custom to the dissemination of Norman Lockyer's theories [though it predates that - see last year's essay] but hints of a much older tradition proved hard to confirm: "'How long has the custom existed?' I asked a field labourer. 'From the time of the old people - the Druids,' he answered, and I gave it up."

__

William Henry Hudson in 1908 [Wikimedia Commons]

__

Arriving at Stonehenge in the early hours of 21st June Hudson found about five or six hundred persons gathered, "mostly young men on bicycles who came from all the Wiltshire towns within easy distance, from Salisbury to Bath [Bath to Stonehenge is about 35 miles!]. However, he thought "the crowd was too big and noisy, and the noises they made too suggestive of a Bank Holiday crowd at the Crystal Palace." As to the main event, "a ribbon of slate-grey cloud… made it evident that the sun would be hidden at its rising at a quarter to four." The crowd meanwhile "sang and shouted", set about the capture of a rabbit that had been unearthed just outside the enclosure (fortunately "earth compassionately opened and swallowed poor distracted bunny up"), and sat and stood on the fallen trilithon behind the altar-stone "packed together like guillemots on a rock", but "cheated by that rising cloud of the spectacle they had come so far to see [they] began to be very obstreperous."

__

Meanwhile the motorists were arriving: "important-looking persons who had timed their journeys so as to come upon the scene a little before 3.45"; and as each gentlemen "appeared within the circle of stones, especially if he was big physically and grotesque-looking in his motorist get-up, he was greeted with a tremendous shout." Hudson was happy to join in: "after all we were taking a very mild revenge on our hated enemies, the tyrants of the roads." But later, at the morning service in Shrewton, he wishes the priest "could have said that it was as irreligious to go to Stonehenge… to indulge in noise and horseplay at the hour of sunrise, as it would be to go to Salisbury Cathedral for such a purpose."

__

In contrast to the exhaustive accounts of 1908, in 1909 the Wiltshire Times offered only the curt report that "There was, as usual, a big crowd to see the sun rise, but not a gleam of sunshine rewarded them, the sky being very overcast." Further down the page another article was headlined: "Cold Midsummer. Unsettled Weather Likely for a Fortnight."

__

However, 1910 was a different matter. For the first time in years the rising sun (almost) made an appearance… The Daily Mail reported that again some 2000 people were there, including all kinds of vehicles and large numbers of men from the military camps [they had quickly picked up on the tradition, it seems]. Technology and commercialism were both starting to intrude: "An enterprising coffee-stall proprietor did a roaring business… whilst one tourist brought in his motor-car a capital gramophone and scared the ghosts of the old Druids with up-to-date songs and marches." The sun rose above some low cloud at 3.50, shining "over the pointer through the great arch and on to the altar" although a number of people had left at the actual sunrise time a few minutes previously, and "consequently missed what was described as the finest sight seen at Stonehenge for many years…" Meanwhile the Bath Chronicle described a "Bath Party’s Midnight Drive to Salisbury Plain" as "A Magnificent Excursion", giving the trip a column and a half. The novelty was that "two motor ‘buses carried [60] pilgrims to the monument." Despite the enjoyment of the trip, in this report the appearance of the sun is played down, "obscured by a bank of greyish clouds until it had risen some way above the horizon…"

__

Summer Solstice, Stonehenge; etching by William Giles (before 1912) [British Museum]

__

In 1911 reports are hard to find, presumably because the coronation of George V on 22nd June took precedence. Then in 1912 reports focussed on the annual summer solstice festival of the ‘Members of the Universal Bond of the Sons of Man’. This was another name for the recently founded Druid Order, led by George Watson MacGregor Reid. The Salisbury and Winchester Journal described their service, which in fact took place on 23rd June: led by a "messenger from Tibet, with his little flock, which included… a Persian gentleman, all clad in eastern robes and turbans." The Confession of Faith, which the paper reproduced, clearly has elements of Zoroastrianism. However, the regular crowd had been present two days earlier for the solstice itself: on the 22nd the Standard and the Daily News both published a post-dawn photo of "pilgrims [turning] their attention to so eminently practical a matter as breakfast." But that week the papers were more concerned about the apparently real possibility of Stonehenge being removed wholesale to America, as Charles Peers, the Inspector of Ancient Monuments, told a Parliamentary committee that "There is nothing at present to prevent Stonehenge from going across the Atlantic".

__

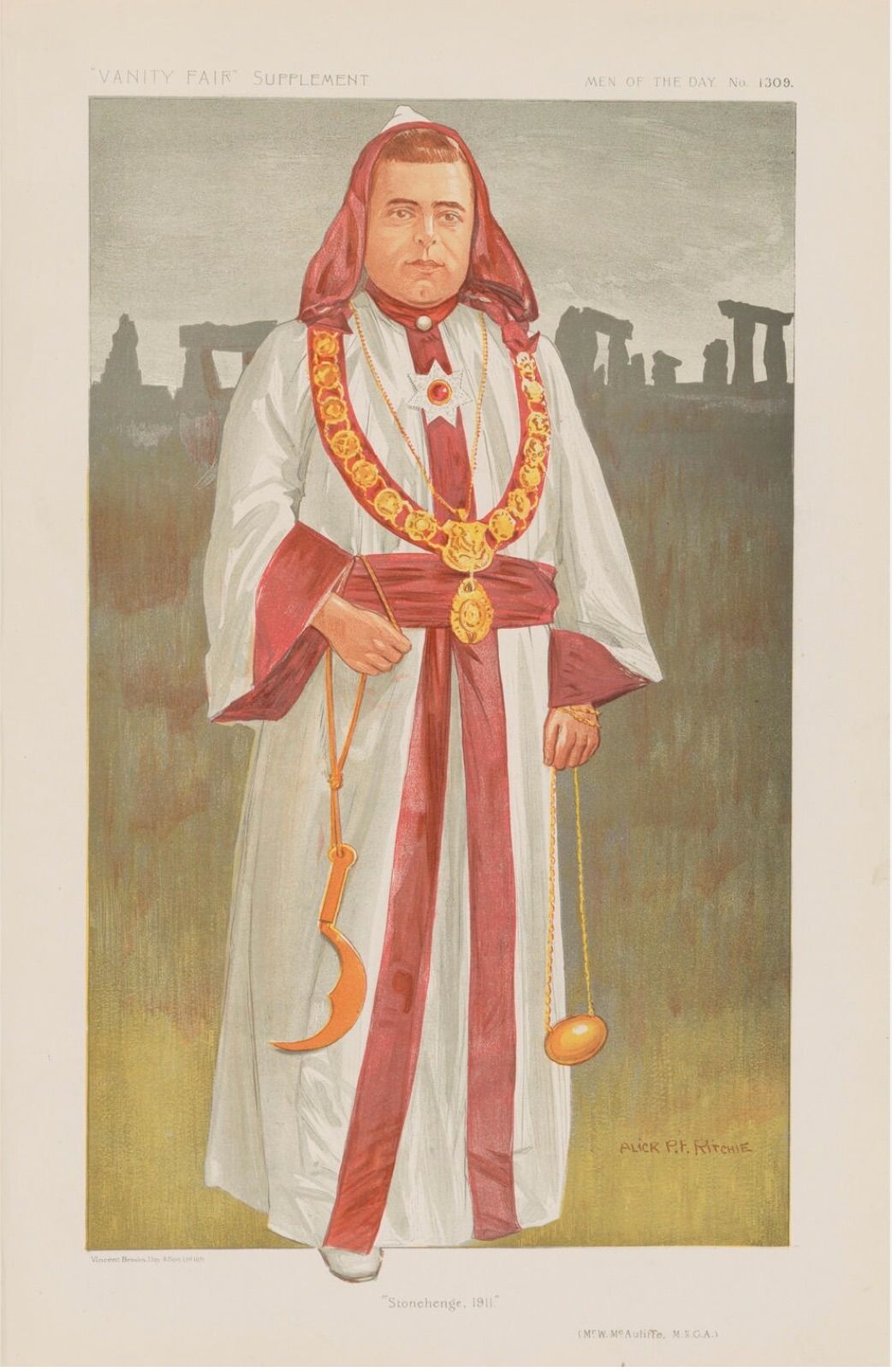

Arch Druid William McAuliffe ('Men of the Day. No. 1309. "Stonehenge, 1911."') by Alexander ('Alick') Penrose Forbes Ritchie; chromolithograph, published in Vanity Fair, 13 December 1911 [National Portrait Gallery]

__

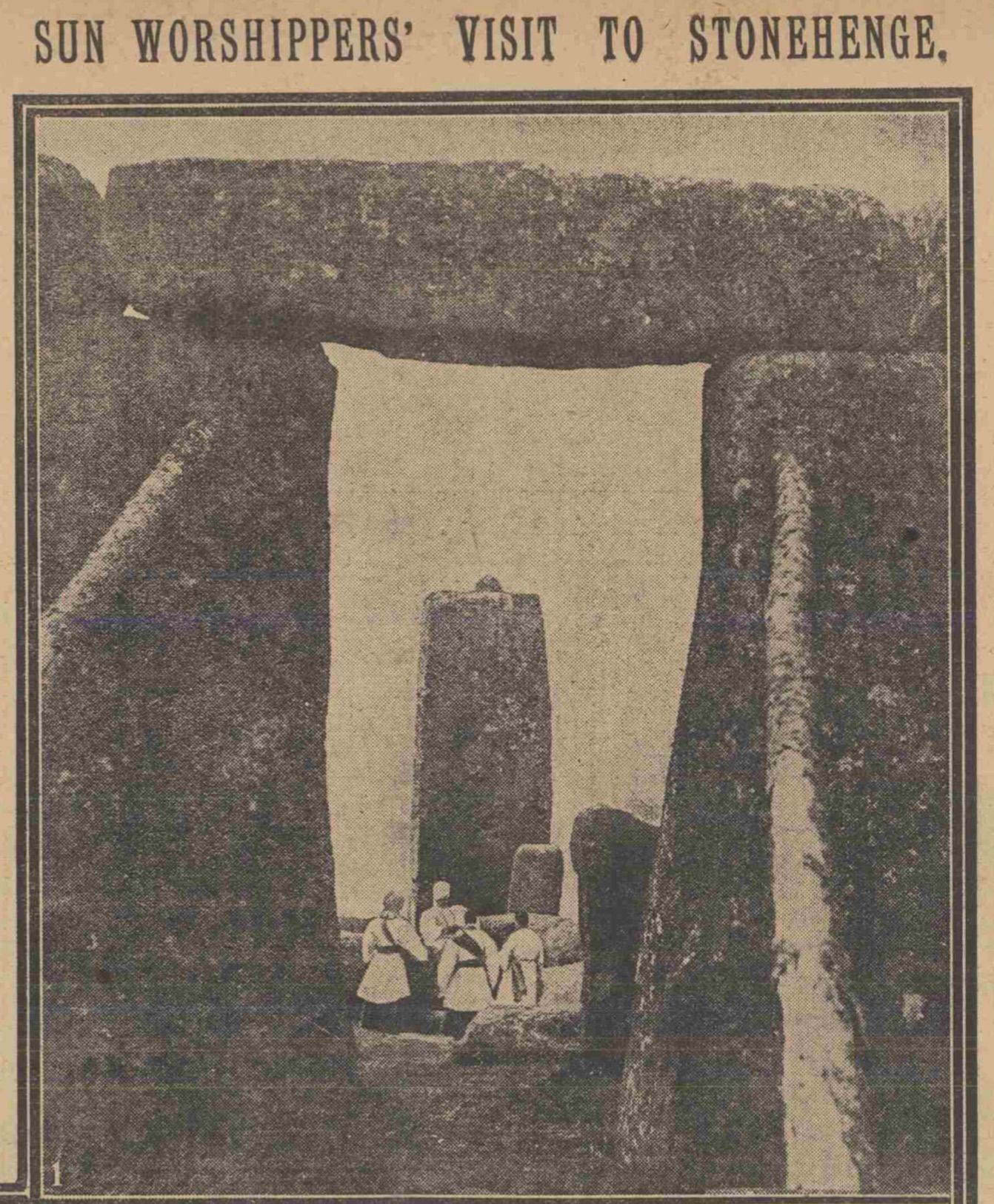

"With the pilgrims at Stonehenge yesterday. (1) At a service showing four of the Sacred Five, the guardians of the Bond" [Daily Mirror, 24 June 1912]

__

"Sun-Worshippers at Stonehenge" [The Daily News and Leader, 22 June 1912]

__

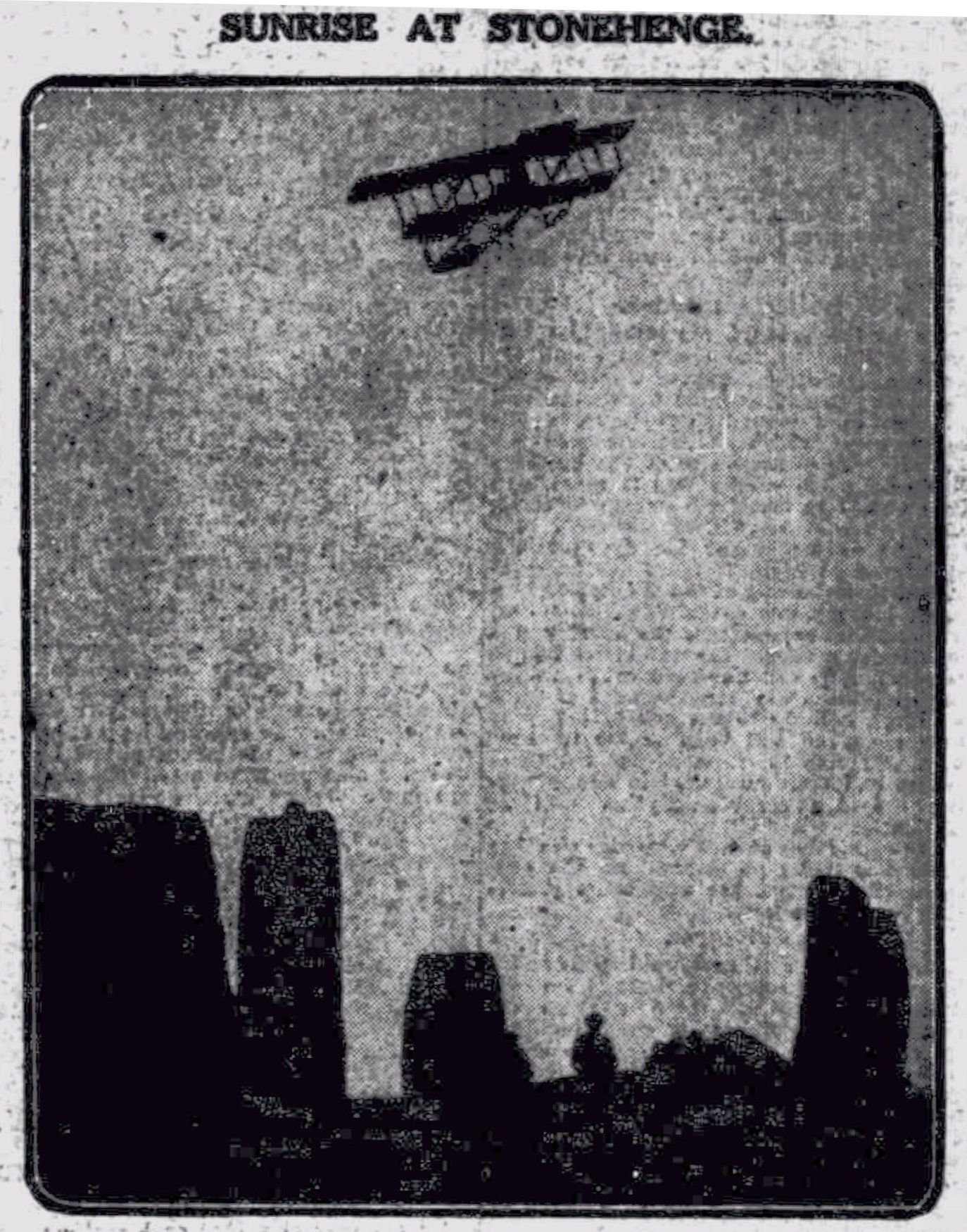

In 1913, a new mode of transport entered the picture, as the Birmingham Gazette published a photo of a biplane over the stones: "The sunrise of Midsummer Day was witnessed at Stonehenge by a number of enthusiasts, who had an aeroplane flight thrown in." Although set in the evening, perhaps this inspired a poem by the Canadian Edmund Kemper Broadus entitled ‘An Aeroplane at Stonehenge’, published in October that year:

__

... And then, from the heart

Of that age-wonted stillness sprang and grew

The iterant throbbing of an aeroplane;

And over our Druid world the marvel sped

And vanished...

__

Sunrise at Stonehenge [Birmingham Gazette, 23 June 1913]

__

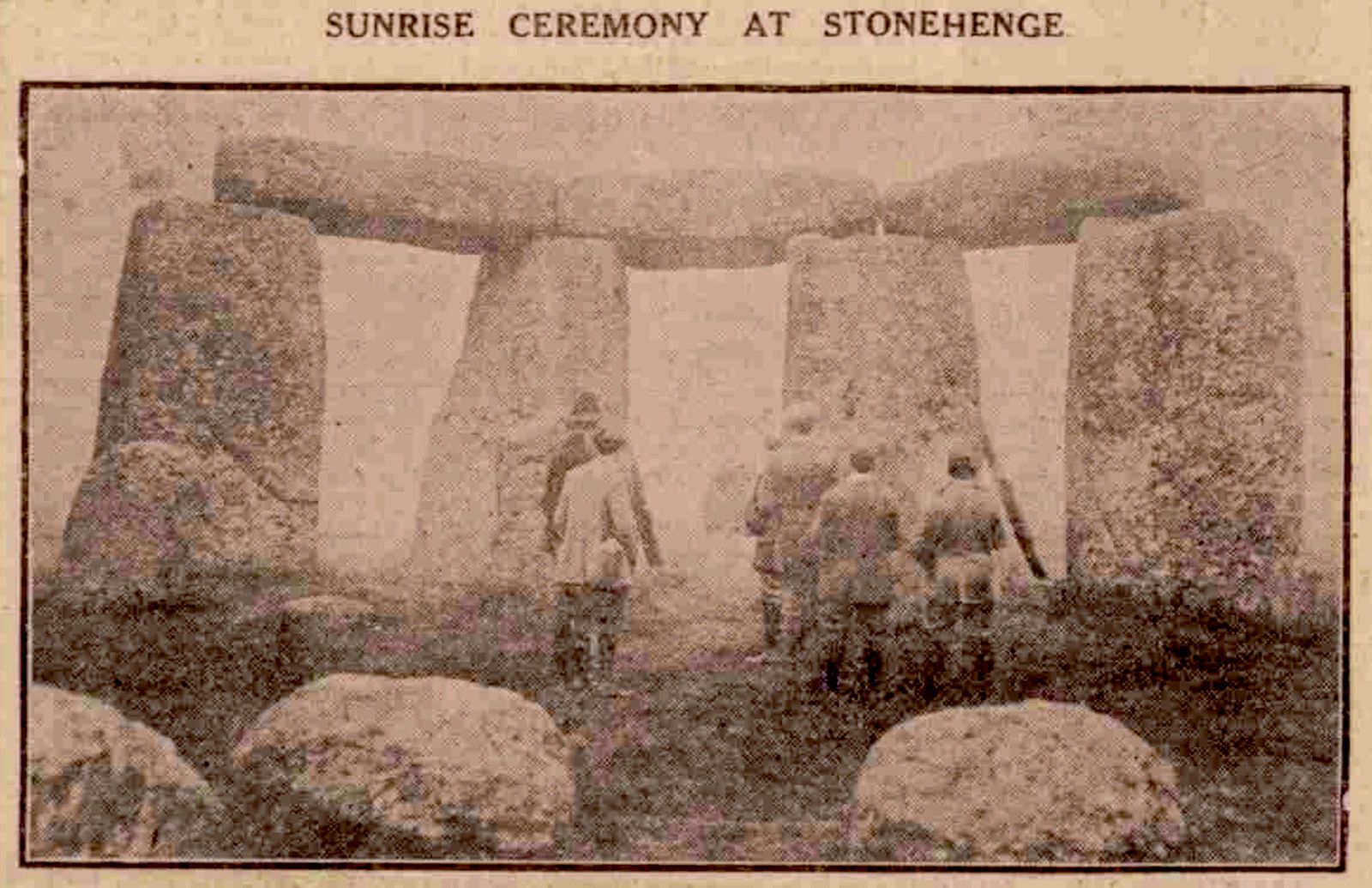

Meanwhile on the ground, the Leeds Mercury carried a photo of some of the "large number of people gathered at Stonehenge at dawn." However, the Wiltshire Times reported "The Usual Disappointment": "two or three hundred sun-worshippers" who "came from all parts, in motor char-a-bancs, motor cars, horse-drawn vehicles, on motor cycles, ordinary cycles, and on foot… were, as usual, disappointed, for the sun rose coyly behind a veil of mist." The price of entry was a shilling [equivalent to £5 today in terms of prices, or £20 in terms of wages]. One London journalist was unimpressed with the value: "after this morning’s lamentable failure to supply goods as per contract you shall hear no protest from me if Stonehenge is torn to pieces by wild souvenir hunters from Cincinnati. To sit through the cold night in the mist of a sort of overgrown graveyard and wait for a sun that does not keep its appointment is to understand why the early Druids faded from the face of the land. They must all have perished from double pneumonia…"

__

The correspondent’s guide for the evening was the chief Druid Dr Reid, who "confided to me that to be astronomically correct Monday [23rd June] was the correct day for the ceremony." The "outer circle of sun-watchers", not having paid their shillings, "were debarred from entering within the barbed-wire fence" but enjoyed themselves nonetheless, apparently by singing ‘Waiting for the Robert E. Lee’ [the big hit of 1912]. The chief Druid also made "a solemn protest against paying their shilling." As the sun failed to appear "One apologist suggested that maybe a Suffragette had stopped it, but we snubbed him with silence, and, learning that we could not get our shillings back, we trailed out into the dawn."

__

Sunrise ceremony at Stonehenge [Leeds Mercury, 23 June 1913]

__

The final solstice before the clouds of war descended in 1914 was again marked by real clouds to disappoint a crowd of over a thousand. As the Western Gazette reported, "Rain came on some time before the moment for the sun to appear above the horizon, and the eastern sky being obscured by clouds the crowd were disappointed in the main purpose of their visit." [As an omen, one thinks of Sherlock Holmes: "There's an east wind coming, Watson…"]. Entertainment came in the form of "a lively scene when the Brotherhood, known as the ‘Sun-Worshippers,’ attempted to perform their ritual at the altar stone". Since they had already made a protest against paying their shilling, the police "acting upon instruction by Sir Edmund Antrobus, interfered with their ceremonial" and ejected them from the enclosure. "There was some violent talk of breaking down the wire" but according to the Gazette, talk was all it proved to be. However, the Faringdon Advertiser, which estimated the crowd as about 3000, and notes that the sun did not appear until almost 10 o’clock, reported that a group of "about 400 men and youths" following Dr Read [sic], "endeavoured to rush the entrance" but fell off when policemen hurried to the spot while "at the pay-box… the few constables stood manfully to their guns" [not literally, one presumes].

__

War did not put an end to the solstice celebrations, however. The Shields Daily News reports the "rather unusual circumstances" surrounding the 1915 pilgrimage but it turns out this was because the site was now on the market as part of the Amesbury Abbey Estate. Dr Macgregor Reid and some of his followers returned to Stonehenge, which provoked further disagreement with the police, "leading to two ejections from the circle and an indignation meeting by the Druids on the open down". The Salisbury and Winchester Journal reported that Dr Reid "said there had been a prophecy that one day three of the stones will fall, and with the fall of the stones a child will be born in Europe, with whom will come a restoration of the law, and behind him the peoples of Europe will unite and march to victory." The conservation work of the 1920s must therefore have served not only to put an end to further collapse of stones, but also to the triumph of "justice and truth… throughout the world"…

__

However, in 1915 there was one difference from the previous year: "The sunrise was one of the clearest seen at the summer solstice for many years, and the early rays of the sun illuminated the Sacrificial Stone as they had not done for over 10 years." The Hampshire Independent reported a crowd of several hundred, many of whom camped on the Plain for the night. "The sun… was a few minutes late peeping above the horizon… but the secondary sight - the sun’s rays shining between the two gigantic monoliths facing the east and lighting up the recumbent stone - was witnessed with a clearness unknown for over a quarter of a century". In fact it had been 28 years, according to The Salisbury and Winchester Journal, which provided some description of the crowd’s activities on a warm night: "An indefatigable violinist attached to a party encamped at one corner of the enclosure poured out a selection of tunes almost without ceasing. A new feature in the night’s watch was the steady gleam of the lights of Larkhill Camp upon the eastern horizon." As soldiers from the camps began to arrive, "the favourite song, ‘The Old Shakes,’ was sung with a correctness and taste that betokened men of musical education among the new Army… The baritone was succeeded by a tenor, who sang the plaintive ‘Annie Laurie’" and later "the soldiers, prompted probably by the thought that they might not all be able to again assemble at Stonehenge on midsummer morning, joined hands and awoke the echoes with ‘Auld Lang Syne’."

__

After this, solstice news is sparse until after the War. In 1916 there were fewer people present than usual, according to the Western Daily Press, but the crowd included "a great addition of military from the camps of Salisbury Plain". However, you cannot expect a clear sky two years running and accordingly "a heavy mist prevented penetration of the requisite rays of the rising sun." On the other hand there was good news for the Druids, as the new owner of Stonehenge, Mr Chubb, had "without agreeing to the correctness or otherwise of their form of worship, assented to the ritual taking place within the enclosure."

__

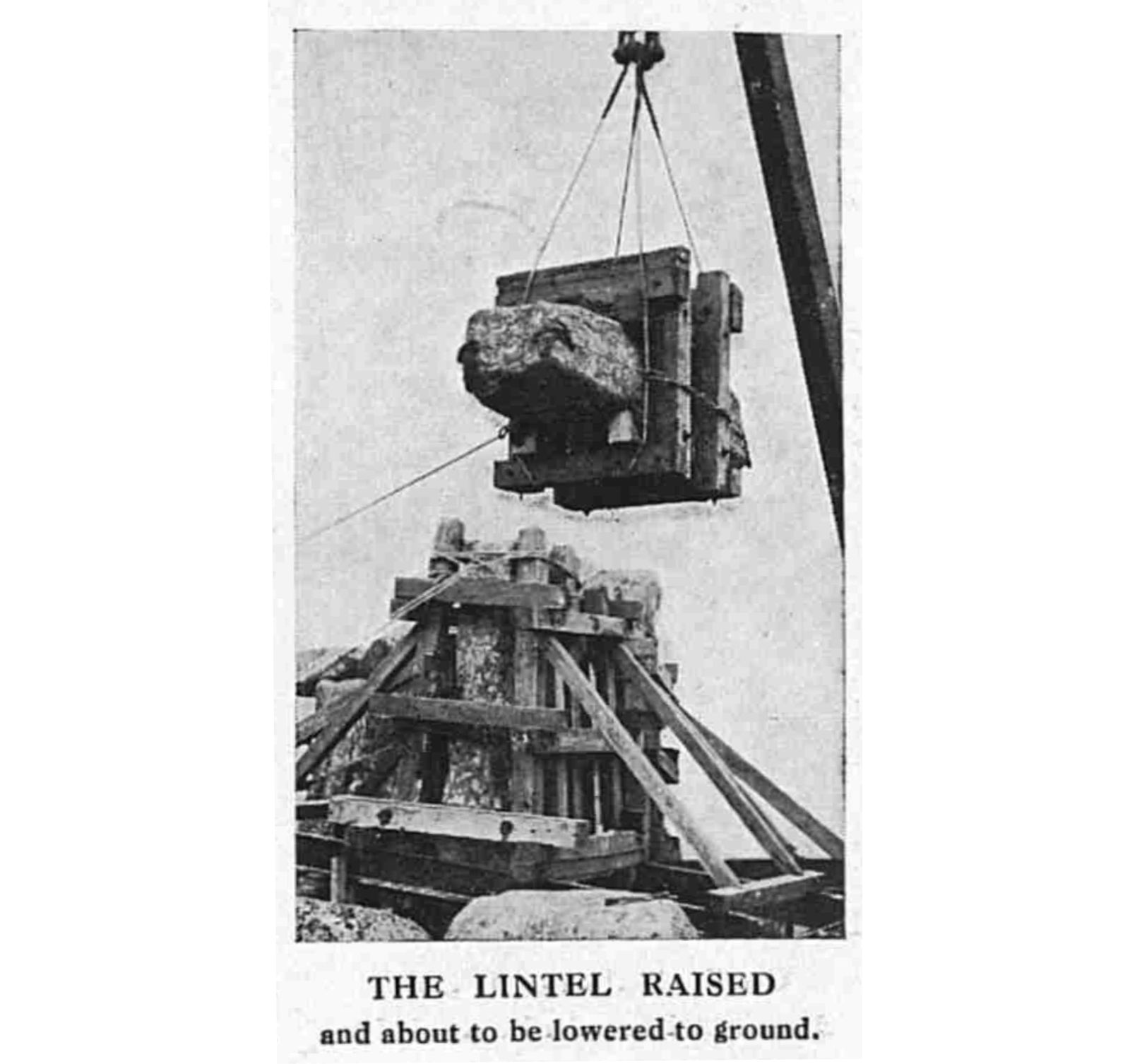

The next reports do not occur until 1920, by when Chubb had donated Stonehenge to the nation and restoration works were underway, as pictured in The Graphic on 26th June 1920. The Daily Mirror reported (with a photograph) that "modern druids held a service in picturesque costumes" on 22nd June and the Bath Chronicle records that two members of the Bath and West of England Motor Club made "the midnight run to Stonehenge", one solo motorcycle and a combination. They seem to have arrived more by luck than judgement, as the Club failed to provide a guide for the run and the party was reduced to "climbing various signposts" in order to find the way.

__

The following year the Gloucestershire Chronicle reported "Another Disappointment at Stonehenge" when "Fully 250 people gathered at the stone circle at the appointed hour and minute, but were doomed to disappointment" with clouds holding the sun until 5 o’clock, meaning it had been "a number of years since the spectacle was witnessed."

__

"The Lintel Raised..." [The Graphic, 26 June 1920]

__

"Through the Ages - A custom which has been handed down from the ancient Britons was revived yesterday at Stonehenge" [Daily Mirror, 23 June 1920]

__

So we reach the solstice of almost exactly a century ago - it was on the 22nd - and it was a good one. Though numbers remained lower than they had been before the War, in 1922 the Westminster Gazette reported that crowds of people witnessed "the first time the sun has shone on the altar stone on a Midsummer Day morning for about ten years", with many visitors travelling by motor coach from as far afield as Brighton and Bristol. About 30 members of the Bath Motor Club made the run this time, among a crowd of two or three hundred. Although "Followers of the Ancient Druids made no demonstration this year… A party of military officers, dressed in long white robes and wearing false beards… gave a humorous representation of a supposed Druidical service." As in 1910 and 1915 the sun did not appear at the exact moment of sunrise, but it was to be seen "within half a minute of sunrise", according to the Wiltshire Times, or as the Bath Chronicle put it, "just a little out of place, and those who saw it felt themselves well rewarded for being present…"

__

What does this social history of the solstice celebrations, seen through the eyes of the press, tell us? Plenty, I think: that tradition keeps being reinvented and rediscovered; that there is an uneasy but inseparable connection between ancient custom and modern technology; that there is something magical about Stonehenge that draws people to it, even in wartime, as must have been the case for millennia; and that there is no time and place better suited to that most traditional of British customs, complaining about the weather.

__

Hoping everyone going to the stones this year feels as well rewarded as the spectators of 22nd June 1922!